A Forest for the Trees

By Stephen Leahy

More than one tree has fallen in the world's forests, but many people heard. Consumers can now buy wood products from certified sustainable 'community forests' in the Third World.

Imagine you are walking through of a hectare of forest - it doesn't matter what kind of forest. Take your time and look around. A hectare is a sizeable piece of land - 2.5 acres for those of us who still don't think metrically. How many trees do you see? The number would vary depending on the terrain you're hiking in, but let's agree there'd be a lot of trees.

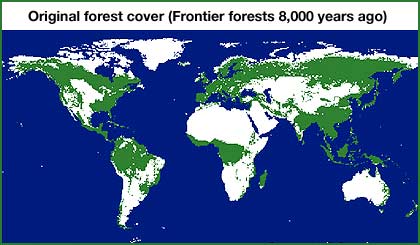

Keep that 'lots-of-trees' image in mind. Every year, 15 million hectares of forest - an area twice the size of New Brunswick - are clear-cut. This annual harvest cuts deeply into the 20 to 30 percent of original forest that remains in large tracts on the planet. Forests have all but vanished in 87 countries.

Satellite photos confirm what we know from our walk in the woods: forests are vanishing. Even in the world-renown 'once-threatened but now supposedly saved' Amazon, deforestation is getting worse.

The root of the problem of the planet's disappearing forests is a global economy built on the foundation (some might say fantasy) of an endless and relatively cheap supply of natural resources. This economic system fuels a demand for wood and wood products such as paper that's expected to double in the next 50 years.

And that fuels the chainsaws of the Third World. Fortunately, while you and I are part of the problem as wood users, we can reduce our wood consumption and be part of the solution as well.

We can now buy wood products that are a cut above, harvested from forests certified to be managed in balance with the environment, thanks to an international organization called the Forest Stewardship Council. Many of the sustainable forests the Council endorses are in the Third World, and are community owned and operated.

Some of the community woodlots have even been re-grown on lands long deforested.

These forests of the future offer practical and inspirational examples of working with an ecosystem instead of merely exploiting it. A tree did indeed fall in the forest, but somebody heard.

A TREE FALLS IN THE FOREST

Eight thousand years ago forests dominated the Earth's landscape. Today's great deserts - the Sahara and the Gobi for example - were once temperate forests. Even the barren, rocky soils of the Middle East were famous for their magnificent cedar forests.

But wood was a necessity for survival and after local trees were consumed, empires fell unless they were powerful enough to exploit far-flung forests. For a thousand years Egypt's pharaohs imported huge cedar logs from Lebanon to make their barges and ships, their temples and palaces.

'Cut and run' forestry hasn't changed much other than an immense increase in scale and global reach. International trade in wood fibre - particularly paper - has quadrupled in the past 40 years.

The United States, with only 5 percent of the world's population, consumes 30 percent of the world's paper. Each year industrial countries use an average of 164 kilograms per person, while developing countries use just 18 kilograms per person. Specifically, the U.S. devours 335 kilograms per person per year, Japan 249, Canada 229, and Germany 192.

By contrast, Brazil uses 39 kilograms per person per year, China 27 and India 4. However, usage is growing rapidly in some developing countries. For example, between 1980 and 1997 consumption in Indonesia rose more than seven-fold, in China more than five-fold, and more than four-fold in both South Korea and Thailand.

While many countries have enacted laws to protect their forests, regulations are simply not enforced, according to the World Resources Institute's Global Forest Watch (GFW). By combining on-the-ground local knowledge with digital and satellite technology, GFW is tracking what's happening to the world's remaining forests. The news isn't good:

- In Indonesia, about 70 percent of timber production is from illegal logging.

- In Central Africa, logging concessions cover more then half of the world's second largest tropical rainforest.

- In Chile, government policies encourage people to clear native forests that are thousands of years old to make way for plantations of exotic (and more lucrative) species. As a result, the prehistoric araucaria forests, and the alerce tree, the second oldest living tree in the world, are endangered.

- In Venezuela, logging and mining practices threaten one of the most pristine forests on the planet.

"Much of the threats facing the remaining intact forests boil down to bad economics, bad management and corruption," said Dirk Bryant, founder and co-director of GFW.

DIDN'T WE ALREADY SAVE THE AMAZON?

Brazil's Amazon forest could vanish by the year 2020, according to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Despite worldwide attention and its importance as a centre of biodiversity, the Amazon still has the world's highest rate of forest destruction - averaging almost two million hectares a year from 1995 to 2000.

And it will get worse if the Brazilian government goes forward with its "Advance Brazil" plan to invest over US $40 billion in new highways, railroads, hydroelectric reservoirs, power lines and gas lines in the Amazon over the next few years.

Brazilians and their government are concerned about conservation and have enacted strict conservation laws, acknowledges Thomas Lovejoy, Chief Biodiversity Advisor to the World Bank. But Brazil suffers from the seemingly universal dilemma of semi-independent government departments doing their own thing - road building, economic development - without considering the long-term impacts, says Lovejoy, a pioneering tropical biologist who has worked in the Amazon since 1965. "We have the same kind of problems in America."

The history of the Amazon clearly shows that new roads lead to colonization, logging, hunting and land speculation. Third World countries will continue to develop in this way - who are we in the First World to say they can't do what we've already done - but the impacts on the environment can be worse than expected.

"Cutting up the forests into fragments, even large ones, increases their vulnerability to fires and edge [development] that creates ongoing degradation of the forest," Lovejoy says.

The people moving into the Amazon should be encouraged to live in urban areas, not in forested areas as homesteaders, he adds. And there must be more thoughtful and integrated forms of sustainable development.

THIRD WORLD CHAINSAW MASSACRE

The World Commission on Forests estimates that the current rate of global deforestation results in 15,000 species becoming extinct each year. The Commission was formed after the 1992 United Nation's Rio Earth Summit when world leaders finally acknowledged that forests were in trouble.

The chopping down of an area twice the size of the province of New Brunswick every year has profound implications for us all. "It could change the very character of the planet and of the human enterprise within a few years unless we make some choices," a 1999 World Commission report concludes.

And the consumption of wood and paper products in the First World/Developed World/North (whatever you choose to call it) is largely what fuels the chainsaws of the Third World/Developing World/South. Reducing our consumption will take the pressure off forests and allow time to make the transition to more sustainable forestry practices. While reducing and reusing are preferable to energy-intensive recycling of paper and wood, all 'wood-wise' efforts are necessary.

Reducing the North's overall consumption of the South's natural resources and closing the gap between the rich and poor must also happen if there are to be any tropical forests left. Illegal logging of tropical hardwoods is often the only way impoverished people can feed their families.

JUDGING A TREE BY ITS LABEL

The good news is that there is rising consumer awareness that wood products ought to come from well-managed forests. Many big forest companies now claim to be sustainable and slap 'green' labels on their products. But how do you know if the claims are true?

The strongest and most reliable system of certification is an accredited body called the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). FSC is the only system that globally tracks products from the forest floor all the way to the retail shelf, a process known as "chain of custody" monitoring.

An FSC logo on a wood product means it came from a forest that meets the highest environmental and social standards. Done right, for example through careful 'selection logging,' timber production can support important conservation values such as biodiversity, water quality and the rights of indigenous peoples

The appeal of the FSC logo program has prompted companies including Home Depot, DIY and IKEA to adopt policies indicating a preference for FSC certified products. The Council has also earned the endorsement of mainstream environmental organizations including the World Wide Fund for Nature, World Resources Institute, Greenpeace, Natural Resources Defense Council and the Sierra Club.

While significant, only 25 million hectares are currently FSC forests. (Bolivia is the world leader in certified tropical forest with one million hectares, thanks to the strong support of the country's forestry sector.) However, 30 large corporations hold 120 million hectares of the world's best remaining forests, little of which is FSC certified.

But consumer demand for FSC products is increasing worldwide. In the Netherlands, for example, 68 percent of the timber purchased is already FSC certified. The notion of sustainability has taken root.

A CUT ABOVE

The forests of the Sierra Norte mountains in the southwest Mexican state of Oaxaca are home to a unique mix of trees. Pine-oak forests, cloud forests and mossy tropical forests blanket the region. "It's a very beautiful area," says Caitlyn Vernon of the Falls Brook Centre, a New Brunswick-based sustainable development organization active in the Sierra Norte.

But like many natural areas, it was falling to the cutting edge of mass logging. Fabricas de Papel Tuxtepec S.A., a former Canadian pulp company in partnership with the Mexican government, owned the timber rights in the region from 1957 to 1983. Deplorable logging practices left valleys filled with unwanted logs, eroded hillsides and ruined watersheds.

There was no reforestation and little of the millions of dollars earned remained with the local people. It took a prolonged struggle by indigenous communities to get the timber licenses overthrown so they could take control of their own forests in 1983.

They formed a co-operative called UZACHI to manage their forests for the long-term, and to keep the money in the community. "People are already seeing the benefits," says the Falls Brook Centre's Vernon. "They have clean water again. They're happy and proud of what they managed to accomplish."

Local people are trained as forest technicians, forest engineers and biologists. Logging is only done on 40 percent of the total 26,000 hectares. There are tree nurseries of local species for reforestation. Conservation and preservation of biodiversity are high priorities.

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certifies these forest practices as sustainable. There is no illegal cutting and everyone shares in the natural wealth of the forest. Responsibility for protection and management is shared widely and official roles rotate through different members of the community every three years.

They're also looking beyond timber, adds Vernon, including the planting and harvesting of forest-grown mushrooms, orchids and other epiphytes. Finished wood products such as children's toys are being made to increase the 'value-added' of the forest to the community.

Eco-tourism is part of the push for diversification. In just a few short years, the area has become something of a mecca for people around the world wanting to learn how to do sustainable community-based forestry the right way.

Based on their work with UZACHI, the Falls Brook Centre is now developing guidelines for sustainable harvests of ground hemlock and balsam fir for Canada's forests. Falls Brook also has a shiitake mushroom growing demonstration site in their New Brunswick forest.

"UZACHI is an inspiring example that can be successfully replicated throughout the world," says Vernon.

Another inspirational case study can be found on the island of Chiloé, a couple of thousand kilometres south of Mexico's Sierra Norte. Lying off the southern coast of Chile, Chiloé is home to 150,000 people in an area approximately 180 by 50 kilometres.

Once entirely forested, only 50 percent of the diverse temperate rainforest (similar to the coastal forests of British Columbia) remains. Unlike mainland Chile, which exports huge volumes of lumber and pulp, all of the wood here is used domestically. It's a cool temperate climate, so most wood goes to cooking and heating. The island is also known for its 150 wooden churches, some more than 150 years old.

The citizens of Chiloé are small landholders who farm, fish and log to survive. Without proper management, the remaining forest is slowly being eaten away.

In an effort to reverse this decline, the Chilean government invited Canada to bring its successful 'Model Forest' program to Chiloé. The Model Forest (MF) is a process for getting everyone in a forest area to develop a consensus-driven partnership to achieve social, environmental and economic sustainability. It's a Canadian idea being put into practice in a number of countries through the International Model Forest Network.

Sixty Chiloé communities are now involved, covering nearly the entire island. "The people have very good knowledge of their forest but don't know enough about ecosystem functioning," says Sylvain Legault, a CUSO cooperant and the only non-Chilean involved in the Chiloé Model Forest.

For hundreds of years people cut whatever they needed, assuming there'd always be enough, says Legault. The first thing was to bring awareness that their lands need to be managed sustainably in order to have a forest for the future. Communities are learning how to plan and manage their forests for the long-term.

Financial incentives from the Chilean government help put these ideas into practice. Experts are brought in to teach forest management techniques. International funding has also helped integrate the indigenous community into the management of the Chiloé National Park.

There is a new emphasis on non-wood products such as honey and hazelnuts. "Local groups also see eco-tourism as an income source," adds Legault.

A new environmental education centre has been an invaluable tool in understanding resource management issues and to improve decision making on the use and conservation of local resources. Other projects include a local geographic information system, and the development of island-wide indicators of sustainable forest management and development.

Positive indicators include an increase in both a community's income and the area covered by forest.

The model forest idea was transplanted successfully on the island. As Legault of CUSO says, "Communities are very strong here. They've resisted offers from resource extraction multinational companies."

FROM THE ROOTS UP

Tropical forests grow in relatively poor soils and once the trees are cut, the strong sunlight turns the land into hard-packed earth. Once the forests are gone, it is very hard to bring productivity back to the land, says Jean Arnold, of New Brunswick's Falls Brook Centre, a Canadian sustainable development organization.

So getting some kind of cover on the ground is crucial. In Nicaragua, vanilla vines are used to help shade deforested areas or depleted coffee plantations. The vines also help retain some of the rainwater that causes erosion and flooding. And, just as importantly, the vanilla can be sold.

In Sri Lanka, there is a broader process at work helping to restore degraded and even disappeared forests. Called "analogue forestry," the idea is to restore the diversity and ecological functions of original forest ecosystems by using a combination of planting, natural regeneration and reintroduction of flora and fauna. The end result is (hopefully) a healthier forest and a wide range of marketable products.

Developed more than 25 years ago by the Neo Synthesis Research Centre, there are now analogue forests throughout the world. The main resources needed are land, time and knowledge. The investment in plants and trees is relatively low, as most species used are indigenous and locally available. As an analogue forest matures to resemble a forest of the past, biodiversity increases, which in turn helps soil conservation and water quality.

A healthy environment is not just important for mother nature. When communities can no longer depend on the forest for survival, their children drift to urban areas, further impoverishing and isolating rural areas. Lack of interest and commitment to the land leads to more environmental degradation, says Arnold of Falls Brook.

But restoration is only possible when local people can get some immediate benefit for their efforts - their survival depends on it. Fruit, berries, nuts and spices are usually the first things planted. These 'forest gardens' often support production of 20-30 different crops, and farmers can access fuelwood and local building materials too.

There is also a certification process for products such as teas, coffees, nuts, spices and syrups that are sold in health food stores in Europe and elsewhere.

Ranil Senanyake of Neo Synthesis believes sustainability will only be achieved through local land tenure. Local communities need to have ownership over the rural agricultural and forest lands in their area. Instead of governments developing industrial pine or eucalyptus plantations to meet wood needs, they should encourage communities to plant and manage multi-species forest plantations that mix native tree species with environmentally appropriate exotic timber species.

The analogue forest movement hopes to grow healthy, diverse ecosystems, which will then provide local economic opportunities and grow healthy, diverse communities.

This is the hope of community timber projects around the world. And consumers can use their power to ensure sustainable forests remain a cut above.

Stephen Leahy is a freelance writer specializing in science, the environment and agriculture.

Written May 2002

| Return to Top

|

| Articles Archive

| About Our Times |